| Page 280 |  |

as a draftsman and copyist by the Archaeological Survey of Egypt. He received some training in Egyptology and hieroglyphics at the british museum before leaving for Egypt in 1891.

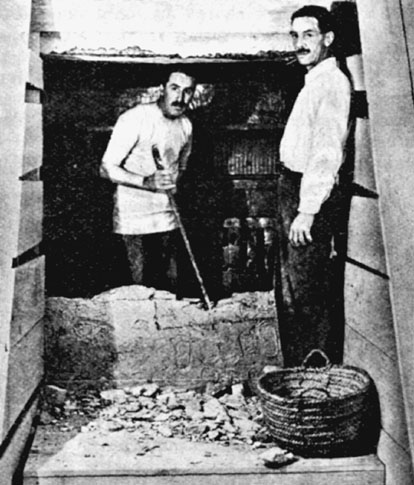

Howard Carter (left) at the entrance of Tutankhamun’s tomb in Luxor, 1922

(Ann Ronan Picture Library)

Carter proved his worth as a competent and committed archaeological draftsman, going on to join sir flinders petrie at excavations at El-Amarna in 1892. Here Carter received training as an excavator from the best Egyptologist of his time. Carter’s rapidly growing proficiency as an excavator and site manager, as well as an illustrator and photographer, was recognized when he was appointed to the post of chief inspector of antiquities in Upper Egypt and nubia in 1900. During the four years he spent in this position Carter undertook important conservation work but was left little time to excavate. However he was able to carry out detailed surveys of the Valley of the Kings, eventually locating the tombs of Thutmosis I and Queen Hatshepsut.

In 1904 Carter became chief inspector of Lower Egypt, but due to a diplomatic row he left the antiquities service and supported himself as an archaeological illustrator and draftsman, buying and selling in the antiquities trade and acting as a guide for wealthy visitors to the Valley of the Kings. In 1909 Carter was hired as expert assistant by Lord Carnarvon, who had decided he would like to try excavating in the Valley of the Kings. The two excavated other sites in Egypt for five years before they were allowed to work in the Valley of the Kings from 1914. World War I put their project on hold; then from 1918 to 1922 they searched the valley for a promising site. By this time Carnarvon had become disenchanted, and by 1922 he had decided this would be their last year. In November Carter telegraphed him in Britain to return: “At last have made wonderful discovery… a magnificent tomb with seals intact…”

Carter’s long training in the practical business of excavating tombs, as well as his skill in recording their contents, made him an ideal person to undertake the task of clearing and documenting the tomb of tutankhamun. But his lack of formal education, his uneasiness about his social position, his obstinacy, and his lack of diplomacy were problematic. Tutankhamun’s tomb transformed him from being an unknown journeyman excavator to a great archaeological discoverer. Clearing and cataloguing the finds changed archaeology in Egypt forever, and strife between Carter and the Antiquities Department lasted for decades. Carter’s greatest gift to Egyptology and posterity was not a monumental scholarly work or new insights into the nature of ancient Egyptian life, but the eight years he spent organizing and supervising the work of a large team of photographers, conservators, and illustrators who patiently catalogued and recorded the contents of the tomb of this minor Pharaoh.

When work on the tomb finally finished in 1932 Carter spent much of his time in Luxor dreaming of discovering the tomb of Alexander the Great, or in London going about his business in the antiquities trade. He received few academic and public honors. He died in London in 1939.

See also

Egypt, Dynastic; Egypt Exploration Society

References

For references, see Encyclopedia of Archaeology: The Great Archaeologists, Vol. 1, ed. Tim Murray (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 1999), p. 300.

Casa Grande, located on the Gila River between Phoenix and Tuscon, Arizona, is a large Hohokam Classic–period ruin. Casa Grande is Spanish for Great House, and this structure is part of a large site with numerous compounds. Prehistoric occupation of the Southwest spans 12,000 years, and Casa Grande is the type-site (an exemplary site; the best example of a type of site) for the Hohokam Classic Period, a.d. 1100 to 1300. Named the first federal reservation for a prehistoric ruin in the United States, Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, the site includes a great house, ball court, and many compounds. No other great houses have been found, although two others may have been built between the Salt and Gila rivers.

The archaeology of Arizona has a long, complex history of exploration and excavation by amateurs and professionals. During the time of discovery in Arizona, research was aided by private funding, the creation of national monuments, and university research institutions. In

|  |