| Page 952 |  |

Nineveh, the great capital of the Assyrians on the river Tigris, became prominent around 700 b.c. during the reign of Sennacherib, who moved his capital there. Notwithstanding its great size and the magnificence of its architecture, Nineveh was sacked by the Medes and the Babylonians in 612 b.c.

First excavated by paul emile botta in 1842, the site is most famously associated with sir austen henry layard, who began excavating at Sennacherib’s Palace in 1846. Layard was fortunate in his assistant Hormuzd Rassam, and the latter developed into an excavator of skill and vigor and took over the excavations after Layard’s return to England in 1851. Between 1846 and 1851, during two major expeditions, spectacular examples of Neo-Assyrian art such as winged bulls and stone wall relief carvings were recovered and sent back to the british museum—which was the major sponsor of the work. Rassam later excavated the famous relief carvings of the royal lion hunt, which also grace that museum.

Of equal importance to the architecture and art works were the numerous cuneiform tablets that made up the Assyrian royal archives in the seventh century b.c., which have since been deciphered. Given the significance of the site, it is hardly surprising that it has attracted constant attention, including the valuable and technically excellent excavations undertaken by sir max mallowan in 1931 and 1932 and the postwar work of Iraqi archaelogists such as Manhal Jabr and the short tenure of the University of California, Berkeley, team under the direction of David Stronach (1987–1990).

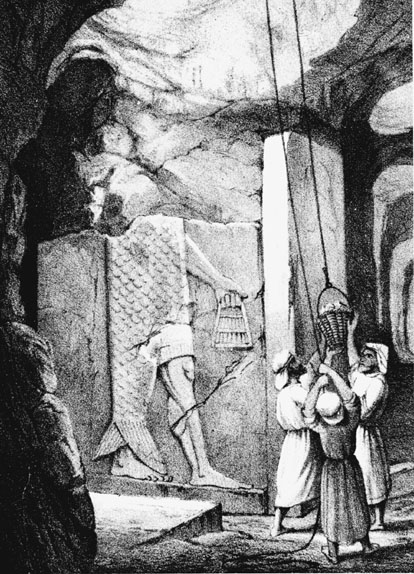

Excavating a low-relief carving of the fish god, Dagon; drawing from Austen H. Layard, Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon; with Travels in Arme-nia, Kurdistan, and the Desert (London, 1853)

(Ann Ronan Picture Library)

See also

References

Russell, J.M. 1998. The Final Sack of Nineveh: The Discovery, Documentation, and Destruction of King Sennacherib’s Throne Room at Nineveh, Iraq. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Novgorod is an urban medieval site that served as the capital of northwestern russia from the twelfth to fifteenth centuries a.d. Located on the northern shore of Lake Ilmen in northwest Russia, Novgorod occupied a strategic position with access to the Volga and Dnieper Rivers and the Baltic Sea; therefore, it connected Russia, western Europe, Byzantium, and the Muslim East (Yanin et al. 1992). The territory of Novgorod, an early state, spread as far as the White Sea to the north and the Ural Mountains to the east, and the city served as the largest center of international and domestic trade in medieval Russia (Yanin 1990).

Archaeologists such as Elena Rybina and Valentin Yanin have conducted research at the site, adding to the 21,000 square meters excavated so far, which still represents less than 1 percent of the total area (Ostman 1997). The waterlogged conditions at the site contributed to the complete preservation of many organic remains such as wood, bone, leather, and birchbark, as well as houses, streets, and medieval topography. Archaeologists have been able to analyze

|  |