| Page 79 |  |

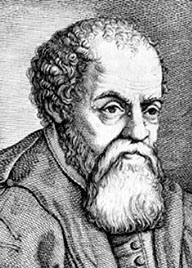

(1522–1605)

A scholar of tremendous range with a focus on natural history and an interest in antiquarianism. Aldrovandi taught medicine at the University of Bologna in Italy in the late sixteenth century. Among his many researches was the natural history of “ceraunia,” thought to be thunderbolts but actually worked flints and stone tools, which he discussed at considerable length in his Musaeum Metallicum (1648). Although another scholar at the time, michele mercati, was persuaded that many of these stones had been shaped by human beings, Aldrovandi preferred to account for them as the result of natural geological processes.

Ulisse Aldrovandi

(Ann Ronan Picture Library)

See also

References

Schnapp, Alain. 1997. The Discovery of the Past (translated from the French by Ian Kinnes and Gillian Varndell). New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997.

Alesia is located at Alise-Saint-Reine in the department of Côte d’Or in France. There were two battles of Alesia. The first, against Julius Caesar, was by a large Gaulish tribal coalition led by Vercingetorix in 52 b.c., and it resulted in the defeat of the latter. The other, which is still taking place today, began in 1850 when scholars began debating the exact location of the famous siege of Alesia, at either Alise on Mount Quxois in Burgundy or Alaise in the department of Franche-Comté, the two most favored sites for this great event. However, tradition also provided the scholars with another site to dispute, the village of Alise-Saint-Reine, which had replaced a Gaulish oppidum (fortified town) with a Gallo-Roman town and which, in fact, is the real site of Alesia. In the ninth century a.d., scholars had recorded this link, but it had been forgotten by the Middle Ages. In 1838, a military officer making a relief map of the site of Alise was struck by its coincidental resemblance to Caesar’s description of Alesia. Several years later, the people of Franche-Comté, supported by the relief map and the analysis of Caesar’s troop movements, debated this claim and proposed Alise as the alternative.

With the encouragement of Napoleon III, soundings were made around Alise between 1861 and 1865, and they revealed the traces of pickax diggings made during a Roman, Gaulish, or German siege. The siege pits corresponded to Caesar’s general descriptions, and the many remains of arms and coins dated the battle. Pits were dug alongside the basic oppidum and confirmed the existence of a Roman settlement, and a “Gaulish wall” was excavated, but it could have been built after the conquest.

In the years from 1950 to 1990, the corpus of coins, ranging from bronze forgeries of the golden statere of Vercingetorix to coins used during the nineteenth century a.d., was analyzed. Aerial prospecting revealed many traces of the pits, contours, and camps installed by Caesar around the citadel. Excavations by a Franco-German team made Alise, for the scientific world at least, a special reference site for dating other contemporaneous sites and for the study of Roman army camps. The traces of the pits and camps were validated by excavations in the nineteenth century and Caesar’s written descriptions. The pits were laid out on

|  |