| Page 817 |  |

1952. The most significant element of his decipherment was the argument that Linear B was, in fact, an ancient form of Greek. Ventris and Chadwick went on to complete the task of decipherment in the years before the former’s untimely death in a road accident.

It is not without some irony that the first major test of the Ventris-Chadwick decipherment was provided by none other than Carl Blegen, who had returned to Pylos in 1952 and discovered a further 300 tablets. The fact that these could be read, even though they (and other Linear B documents) are primarily invoices and the “paperwork” involved in the administration of palace business, at once brought history closer to the Minoan and Mycenaean world. The fact that the last kings of Crete were Greek speakers has led to a reevaluation of Evans’s argument that the Minoans had conquered the Mycenaeans. It is now thought that the reverse is true and that around 1450 b.c. Knossos was conquered by the same people who ruled at Pylos and Mycenae.

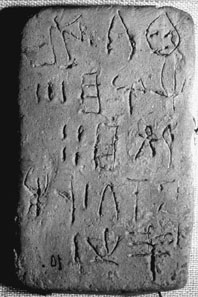

Early Minoan writing

(AAA)

References

Doblhofer, Ernst. 1961. Voices in Stone. London: Picador.

Stone artifacts are studied by archaeologists because they are durable and frequently found on archaeological sites of almost every age. Consequently, much has been written about their analysis and interpretation. This article considers the history of three approaches to the study of stone artifacts: (1) factors contributing to variation in the composition and characteristics of stone artifact assemblages, (2) functionalist interpretations of artifact assemblages, and (3) idealist interpretations of material remains.

Functionalist and idealist approaches reflect a fundamental debate in archaeology about whether humans are passive participants or active agents in their worlds. Functionalist approaches seek to explain the role of artifacts in the evolution and/or behavior of different groups. Idealist approaches seek to understand the knowledge and belief systems of the makers of artifact assemblages. Fundamental to both approaches is an understanding of why recurring artifact forms (i.e., types) exist, as well as the factors contributing to variation in the composition of artifact assemblages.

For much of the twentieth century, archaeologists attributed the similarities and differences between artifact assemblages to a single variable: the cultural idiosyncrasies, or traditions, of different groups of people. The best known work in this regard is françois bordes’s study of variation in Lower and Middle Paleolithic assemblages from southwest France (Bordes 1961). Bordes formulated a typology to describe the sixty-three different tool types (i.e., artifact forms) recognized as regular components of Lower and Middle Paleolithic assemblages. He then characterized the artifact assemblages recovered from the various layers of different rock-shelter deposits in terms of the relative proportion of each made up by those sixty-three tool types. Comparison revealed repeated patterns

|  |