| Page 745 |  |

America, a de facto scientific adviser to the government. The society wrote the charter for the government’s great western exploratory expedition led by Lewis and Clark, and later contributed to the Lond Expedition of 1819 and the Wilkes Expeditions of 1838 and 1842, both of which were anthropological in objective. Under Jefferson’s presidency the APS took an interest in archaeology, linguistics, and anthropology.

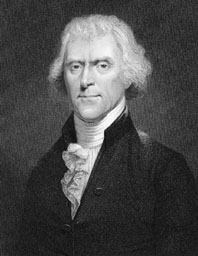

Thomas Jefferson

(Ann Ronan Picture Library)

Jefferson was a pioneer in the study of archaeology, paleontology, ethnology, geography, and botany in America and he amassed a collection of Indian vocabularies that were unfortunately lost. Through the APS Jefferson became associated with the important scientific societies of Europe and America. He was elected in 1801 to the Institute of France in recognition of his reputation in france as an intellectual—and not as a politician. He corresponded with a great many scientists across the world and across America and wanted the best of foreign knowledge to be available to Americans. After his final retirement from politics he helped to found the University of Virginia and he established a school of builders in Virginia and tried to establish formal instruction in architecture. He kept up with his voluminous correspondence and he continued to advise his political colleagues. To reduce his debts Jefferson sold his collection of some10,000 books to the new Library of Congress.

Jenné and Jenné-jeno (ancient Jenné) are successive tell settlements in the upper inland Niger Delta of Mali, and together, they span over two millennia of continuous occupation on the floodplain. Both have been designated World Heritage Sites by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. The forty-five-hectare tell of Jenné is inhabited today by a population of about 10,000.

Historical sources, such as the account of the French explorer Réné Caillié (1830) and local tarikhs (histories written in Arabic), detail the central role that Jenné has played in the commercial activities of the western Sudan during the last 500 years. In the famous “golden trade of the Moors,” gold from mines far to the south was transported overland to Jenné, then transshipped on broad-bottom canoes (pirogues) to Timbuktu, and then sent by camel to markets in North Africa and Europe (Bovill 1968; Levtzion 1973). Leo Africanus (1896) reported in 1512 that the extensive boat trade on the middle Niger involved massive amounts of cereals and dried fish shipped from Jenné to provision arid Timbuktu. Today, the stunning mud architecture of Jenné in distinctive Sudanic style is a legacy of the settlement’s early trade ties with North Africa.

Systematic archaeological research at Jenné began in 1994 with a coring project (McIntosh et al. 1996) and continued with excavations in 1998 on the proposed site of the new Jenné museum. Cultural deposits descended over six meters and began with material dating to the early second millennium a.d.

Three kilometers to the southeast, the thirty-three-hectare mound of Jenné-jeno attracted little attention during the colonial period despite its thick surface carpet of broken pottery and numerous mud brick wall foundations. Scientific excavations in the 1970s and

|  |