| Page 452 |  |

Since 1980 however, Egyptian archaeologists have undoubtedly begun to seek what Smith describes as “new types of information,” and there has been a massive growth of interest in the investigation of data from prehistoric and urban sites. There have also been a few small signs of movement, or at least a recognition of the need for movement, toward more problem-oriented fieldwork (e.g., Assmann, Burkard, and Davies 1987; van den Brink 1988), with some research projects beginning to be specifically designed to answer long-standing cultural or historical questions as opposed to the tendency simply to explore new sites in an indiscriminate fashion.

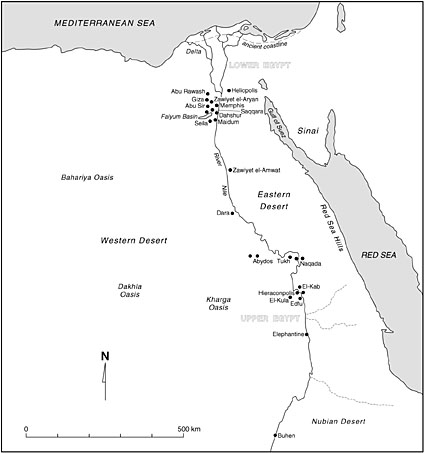

Egyptian Archaeological Sites

One of the foremost problems of Egyptology is the recurrent bias toward data from Upper (i.e., southern) Egypt. Despite the work undertaken at delta sites both in the late nineteenth century and the late twentieth century (see van den Brink 1988, 1992), the prevailing view of Egyptian society and history is heavily biased toward Upper Egypt and dominated in particular by the rich remains of the Theban region. This situation stems partly from the survival of more impressive standing architectural remains in