| Page 389 |  |

to collect and excavate for antiquities, motivated less by academic concerns than by a spirit of acquisitiveness and competition, sometimes enhanced by financial motives. A more circumspect attitude toward the Ottoman rulers of Cyprus might have been appropriate for consular officials like Sir Robert Hamilton Lang, but when official permits were not forthcoming, excavation and the subsequent exportation of antiquities continued nonetheless.

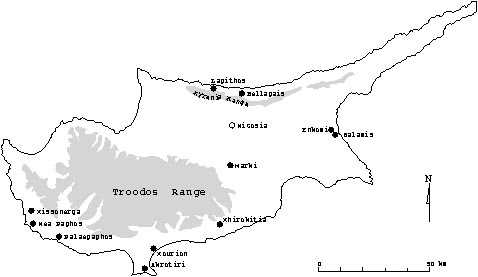

Archaeological Sites in Cyprus

The most flamboyant and active of these early predators was the Russian and American consul, General luigi palma di cesnola. His vast collections, obtained by large-scale plundering of tombs and other sites, were exported from the island after 1870. Most of this material—over 10,000 items—was finally purchased by the Metropolitan Museum in New York City, and part of the deal resulted in Cesnola’s appointment as the first director of that museum. Lavish publications did little to allay scholarly disapproval of Cesnola’s methods and abilities. His brother, Major Alexander Palma di Cesnola, continued the family tradition by excavating in Cyprus in the 1870s for a British collector who subsequently sold the material in Great Britain.

Other consular collectors began to move beyond simple acquisition. Thomas Backhouse Sandwith is generally credited with being the first to attempt to establish a pottery sequence, initially presented in a paper to the society of antiquaries of london in 1871. Most antiquarian activity on the island was more concerned simply with acquisition until a major political development in 1878 led to the establishment of British rule.

Although Cyprus was administered by Britain, it remained a part of the Ottoman Empire until 1914 when it was formally annexed to the British Empire. Initial administration of the Ottoman antiquities laws was inadequate, despite the establishment of a museum in 1883, and the situation did not change significantly for some decades. One immediate reaction to the British takeover was an upsurge of interest on the part of professional archaeologists, especially those based at the british museum. From 1879 onward, Max Ohnefalsch-Richter worked at numerous sites on behalf of the British Museum, which thereby obtained a significant share of the finds. Other British museums also obtained small collections by contributing to the costs of fieldwork.

A major development was the foundation of the Cyprus Exploration Fund in 1887 to provide

|  |