| Page 307 |  |

that this generation was not accustomed to the transference of knowledge at the pupil level. Latcham’s perspective of Chilean anthropology was influenced by classic British empiricism, which was geared toward the systematic arrangement of data rather than to theoretical reasoning, thus promoting an upsurge in the publication of valuable monographs in both material culture and regional archaeology and their trans-Andean connections (Latcham 1928, 1938). More an avid reader than a fieldworker, Latcham incorporated into the National Museum of Natural History his affinity for physical anthropology through studies in ethnography, ethnohistory, ethno-agriculture, and ethno-zoology as well as his own specialty in engineering to benefit the understanding of pre-Columbian metallurgy.

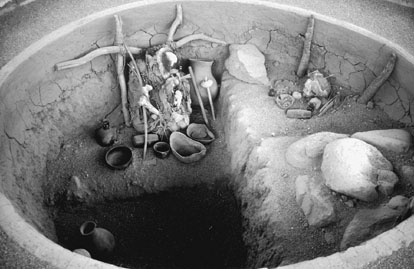

Ancient burial ground, San Pedro de Atacama, Chile

(Chris Fairclough Colour Library)

Latcham did not rely on excavated data, and he was unable to use it with the same detail as Uhle. In this sense, his archaeological principles were intertwined with ethnohistoric sources. He played a leading role in anthropology until the 1940s when his colleague Grete Mostny began her scientific investigations. Mostny had taken refuge in Chile to escape racist persecution in Vienna, and with a doctorate in Egyptology, Mostny would eventually lead the National Museum toward its higher objectives of combining science with popular communication.

Latcham’s work centered on the study of the Mapuche, on physical anthropological studies, and on the compilation and interpretation of archaeological and ethnohistoric data. In addition, he also initiated courses on prehistoric Chile in 1936 at the University of Chile. He rejected proposals that stemmed from historical materialism, thus consolidating the success of the Vienna school in relation to the southern peoples of Tierra del Fuego.

The downfall of the fascist regimes in Europe in 1945 resulted in an influx of migrants to South America, including the cultural historians Marcelo Bórmida in 1946 and Osvaldo Menghin and Vladimiro Male in 1948. These scholars, along with Casanovas and Canals Frau, consolidated the hegemonic movement during times of academic repression in Argentina. The most important representative of this movement was the prehistorian Osvaldo Menghin,

|  |