| Page 213 |  |

which was aired by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) to mass audiences. The global reach of British prehistoric archaeology was also extended by the foundation of the Institute of Archaeology in London (in which Wheeler was particularly influential and Gordon Childe served as the first director). Students from all over the world studied there, learning the techniques that would be used to undertake foundational work in countries as diverse as China and India. A further extension of interest was achieved with the foundation of the journal antiquity by o.g.s. crawford and the transformation of the Prehistoric Society of East Anglia into, simply, the Prehistoric Society.

Notwithstanding the significance of these developments, the period is most notable for the work of Gordon Childe and J.G.D. Clark. Between 1925 and 1956 Childe literally transformed archaeology in the Anglo-Saxon world (and beyond) through a series of classic publications that greatly enhanced both the professional and the public understanding of British prehistory in particular and archaeology in general. But Childe certainly stood on the shoulders of giants, and during his long career he also profited much from the work of those he had strongly influenced (including Piggott and Hawkes). The tradition of rigorous analysis of artifacts from Neolithic, Bronze Age, and Iron Age contexts that provided Childe with much of his British information was developed and enhanced during this period. Renfrew (1972, 12) has rightly identified lord abercromby’s Bronze Age of Pottery of Great Britain and Ireland (1912) as an early example of the British archaeologists’ exploration of the spatial distribution of material culture types (the real potential of which was established by Crawford in Man and His Past).But it was Gordon Childe’s development of the concept of the archaeological culture that provided the core interpretive perspective needed to make such culture-histories plausible. Childe demonstrated the potential of this new way of seeing in The Dawn of European Civilization (1925) and elaborated it in The Bronze Age (1930) and subsequent publications. Renfrew (1972) has also stressed that in the 1930s British prehistoric archaeologists were able to consider the spatial organization of culture in terms of human geography—as expounded by Sir Cyril Fox in his pathbreaking “regional prehistory” entitled The Personality of Britain (1932)—and that this was also a major influence on their practice.

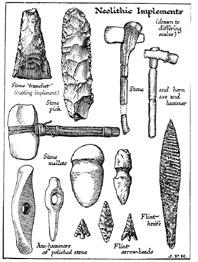

Neolithic implements, drawn to differing scales

(Ann Ronan Picture Library)

Historians of archaeology (particularly Trigger [1987]) have seen the years between the late 1930s and the advent of radiometric dating in the late 1950s as a long period during which Childe’s account of the archaeological culture and the project of culture-history was elaborated. There is merit in this assessment of the period in which change in later British prehistory was almost always explained as the outcome of migrations, invasions, or diffusions—certainly of forces that (along with climate change) lay external to the societies whose histories Childe and others were trying to understand. There is little doubt that Childean archaeology dominated the theoretical landscape of British prehistoric archaeology throughout this period, but there were significant tensions between Childe’s culture-history and the detailed economic and ecological approaches to understanding the archaeology

|  |