| Page 1170 |  |

Elliot Smith’s interests in and thoughts about ethnology and paleopathology, the results of his participation in the Archaeological Survey of Nubia, later led him to theorize that all cultural development—especially agriculture, pottery, clothing, monumental architecture, and kingship—had originated uniquely in Egypt, “the cradle of civilization,” and then Egyptian merchants had carried Egyptian innovations and culture and spread them to the rest of the world. His books The Migrations of Early Culture (1915) and The Ancient Egyptians and the Origin of Civilizations (1923) elaborate these “hyper-diffusionist” ideas and were popular at the time of their publication.

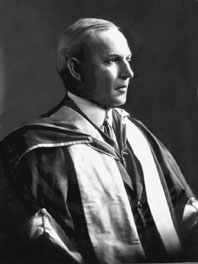

Sir Grafton Elliot Smith

(Image Select)

See also

Piltdown Forgery; Reisner, George Andrew

References

Spencer, F. 1990. The Piltdown Papers 1908–1955: The Correspondence and Other Documents Relating to the Piltdown Forgery. London: Oxford University Press.

Although the Smithsonian Institution (SI) became operational in 1846, its foundation actually stemmed from an 1835 bequest by James Smithson, an Englishman who had never visited the United States. Smithson’s gift of over half a million dollars created one of the most significant institutions in the history of U.S. archaeology as part of one of the world’s leading museum organizations.

Under its first secretary, John Henry, the Smithsonian made a vital contribution to the archaeology of North America when it published Ephraim G. Squier and edwin h. davis’s Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley in 1848. Its influence continued with the publication of Samuel Haven’s The Archaeology of the United States, or Sketches Historical and Biographical, of the Progress of Information and Opinion Respecting Vestiges of Antiquity in the United States (1856). Both works had a significant impact on the history of prehistoric archaeology in North America.

The Smithsonian soon became an important element in the U.S. government’s network of information sources, and its prominence in this arena remains undiminished. Not only would it become a storehouse of national knowledge, it would also use that knowledge in the service of government. In this sense the Smithsonian responded to a thirst for knowledge about the United States and through its work increased the desire for knowledge. This was especially true in the case of ethnology and archaeology. In 1861 the SI published “Instructions for Research Relative to the Ethnology and Philology of America” by George Gibbs, which mirrored the scope and purpose of the famous “Notes and Queries” produced by the British Association for the Advancement of Science. Gibbs’s questionnaire, included in the instructions, was used by many of those undertaking primary ethnological and archaeological research, as well as others, such as missionaries and government agents, who sought a more direct understanding of indigenous Americans. In 1864, the SI sought to gather information about collections of artifacts derived from earthworked archaeological sites known as “mounds” and also about the “moundbuilders” who built them in order to

|  |