| Page 1032 |  |

working on aerial photographic interpretation he was able to do a considerable amount of research on the early prehistory of the subcontinent, which resulted in the publication of several books and papers.

On returning to Britain, he became the new Abercromby Professor in Edinburgh, a post that brought with it a commitment to fieldwork in Scotland and an incentive to research the broader field of European archaeology. The former resulted in the excavation of several important Neolithic sites. The latter led to the publication of a synthetic study of ancient Europe, which examined themes covering prehistory from the introduction of agriculture.

Ultimately, these two imperatives changed the direction of Piggott’s interests. He became more interested in later prehistory and, in particular, the development of wheeled transport and the significance of Celtic art and religion. Interest in wagons, chariots, and horses was a theme that brought together many of his European interests, charting the movement of peoples and the rise and fall of political elites.

Piggott continued as the Abercromby Professor in Edinburgh until his retirement in 1978. After that time, he carried on writing, and a large number of books and papers appeared on many subjects, not just those discussed above. He also developed his interest in the history of British archaeology. In this area, he originally focused on the figure of william stukeley, an individual with an important role in the understanding of the Neolithic period at Avebury, but he later expanded his work to cover the antiquarian imagination of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries.

As his career progressed, Piggott became more and more aware of the limits of archaeological inference. He realized that much of his earlier speculation on the Neolithic period was inaccurate, which was emphasized by the radiocarbon revolution that undermined the typological chronology he had striven so hard to construct. He therefore narrowed the range of his interests in the later part of his career to emphasize the history of archaeology and the technological development of transportation.

References

For references, see Encyclopedia of Archaeology: The Great Archaeologists, Vol. 2, ed. Tim Murray (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 1999), pp. 630–633.

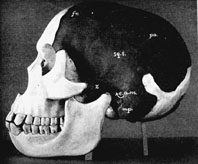

The Piltdown man, one of the most famous forgeries in the history of paleoanthropology, was a composite of a skull and associated skeletal remains discovered in a gravel pit in East Sussex, England. The skull (named after Piltdown Common where it was found) was first unveiled at a meeting of the Geological Society of London in 1912 by Charles Dawson, the discoverer, and Arthur Smith Woodward of the British Museum of Natural History, the professional paleontologist who backed its legitimacy and importance. Based on excavations made at the site by Dawson, Smith, Woodward, and others, crude stone tools (or eoliths) were thought to have been found in association with the remains of an animal that had a large brain but an apelike jaw with “modern” teeth. Coming at a time when skeletal evidence of the physical evolution of human beings was extremely rare, especially from really remote antiquity, the Piltdown discovery gained great notoriety.

Model of the Piltdown “skull,” in fact a re-creation from parts of two animals

(Ann Ronan Picture Library)

As Frank Spencer (1990) has noted, however, from the very first the Piltdown remains were regarded as problematic by some people, but a clear understanding of just how problematic they really were was only gradually revealed. As

|  |