| Page 72 |  |

(1907), Desplagnes presented sketches and photographs of archaeological material, tombs, dwellings, people, modes of transport, and the various environments to be found in the area of the Niger Bend. He conducted excavations at two impressive tumuli near Goundam, where he was posted, drawing attention to the similarity of the burial ritual to that practiced by Sudanic chiefs at the time of the kingdom of Ghana, as described by al-Bakri in the eleventh century (Mauny 1961, 95–97). He described in considerable detail what he observed as he excavated and the objects he found, and his descriptions were accompanied by drawings.

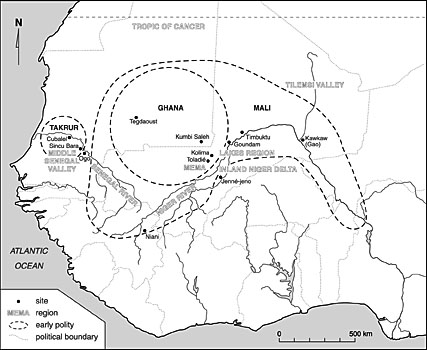

Sudanic Kingdom of West Africa

It would be more than thirty years before French West Sudan again saw that level of quality in excavation and description. In the interim, many sites significant to an understanding of the regional context of the emergence of the kingdom of Ghana were hacked at by bored soldiers, administrators, civil servants, and journalists looking for excitement. Clerisse, for example, who managed to undermine or topple most of the dozens of phalliforme megaliths at Tondidaro within a space of a few weeks (Mauny 1961, 131–134). Huge occupation tells, such as Kolima, were ruthlessly trenched for intact pots and valuable goods. Even the well-intentioned Bonnel de Mezières, in his earnest quest to find the capital of Ghana, managed to plow through five houses, six tumuli, and eighteen tombs at the tell of Koumbi Saleh in March 1914, concluding “contrary to my hopes, I have learned nothing from these excavations and have not been able to affirm that Koumbi Saleh was the capital of Ghana” (Bonnel de Mezières grave 1923, 255).

Fascination with locating the capitals of the