| Page 676 |  |

Susa. In a report to the Royal Asiatic Society in 1850, he suggested that excavations be conducted at the great mound of Susa for the express purpose of discovering more bilingual inscriptions, and he persuaded the British prime minister, Lord Palmerston, to provide a parliamentary grant of 500 pounds for further explorations of the site.

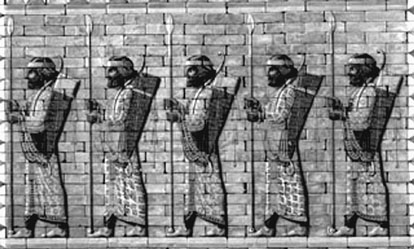

Royal bodyguard, relief from the palace of Darius I in Susa, ca. 500 B.C. of the Persian Kings

(Image Select)

The first scholarly excavations in Iran were those of the British geologist, William Kennett Loftus, a member of a commission formed by the British and Russian governments to arbitrate the delineation of the frontier between Persia and Turkey. In 1850, Loftus and another member of the commission, Henry A. Churchill, visited Susa intending to excavate. Because of local resentment, the visit was brief. The two returned in 1851 along with Colonel W.F. Williams, the commandant of the frontier commission, and they planned the site, identified it through inscriptions as the Susa of the Old Testament, and established the presence of Sassanian, Achaemenid, and earlier (Elamite) levels.

During a trip across Persia in 1881–1882, Marcel-Auguste Dieulafoy, a French engineer, soldier, and architectural historian, visited Susa with his wife, Jane, and upon their return to France, Dieulafoy persuaded the national museums to provide modest financing for excavations. Unlike most of his contemporaries, Dieulafoy was more interested in architecture than museum-quality objects. Thus, from 1884 to 1886, the Dieulafoys worked exclusively on the columned Apadana (Audience Hall), previously identified by Loftus, from which they retrieved spectacular Achaemenid remains. These antiquities became the core of the louvre’s extensive Susa collection.

In 1886, Nasir el-Din Shah (1848–1896), who was aware that the local population was still discontented with the excavations, shut them down, and almost a decade passed before the French legation in Tehran felt it could reopen the matter. In 1895, the French ambassador, Rene de Balloy, finally persuaded the shah to sign a treaty that granted the French an exclusive concession for archaeological research throughout Persia. In Mesopotamia, then under Ottoman control, considerable rivalry between

|  |