| Page 599 |  |

new law in 1928 limited the foreign schools to three excavation permits each. But with the economic problems of the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Greek Archaeological Service was almost bankrupt. For this reason, one of the potentially most exciting sites in Athens, the Athenian Agora, had to be given to the Americans. Between 1927 and 1940, they lavished on the site $1 million donated by John D. Rockefeller alone, quite apart from other sources. Much of the money went for expropriating the land from the several thousand refugees from Asia Minor who had inhabited it since 1922. In spite of gaining independence and control over its own archaeology, Greece could not quite escape the influence of the western archaeological powers.

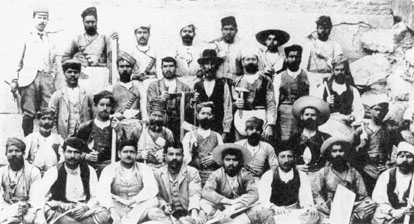

Part of Arthur Evans’s workforce in the Hall of the Double Axes at the Palace of Knossos in 1901

(Ashmolean Museum)

As early as 1852 the German archaeologist ernst curtius began raising money for a new type of excavation at Olympia, one that would not remove archaeological material to other countries but one that would systematically record and analyze this important site. It was only after Schliemann’s more dramatic, if less systematic, work at Mycenae and elsewhere that the Germans (and others) began to appreciate the need for large-scale, well-funded projects. Curtius finally won his funding in 1875, and a treaty was signed between Germany and Greece allowing the German Archaeological Institute (deutsches archäologisches institut––dai) to undertake systematic exploration at Olympia, on condition, of course, that all finds remained in Greece. Stratigraphy and particular find spots were carefully recorded, structures underwent architectural analysis, and the Olympia excavations became a model of the new systematic, scientific excavation methods.

Another result of Schliemann’s massive self-publicity was a sudden interest in the prehistoric period. The key figure here is Christos Tsountas, who followed Schliemann at Mycenae and worked there over a period of more than two decades as well as at numerous other Bronze Age and earlier sites all over the mainland and islands of Greece. Unlike his predecessor, Tsountas set out, not to prove a myth, but to investigate material culture and the development of human society. He achieved his aims partly by remarkable finds, such as an undisturbed fifteenth-century b.c. princely tomb at Vapheio in Laconia, which he excavated in 1889, complete with weapons, jewelry, and gold cups. More pertinently, through the meticulous excavation of a broad range of sites, particularly cemeteries, and the careful comparison of their materials, he was able to put together a broad picture of the development

|  |