| Page 51 |  |

in creating an awareness among the general public of the value of archaeological surveys before old buildings are destroyed and/or restructured.

South African Historical Archaeological Sites

In the early 1980s, an archaeologist from the University of Cape Town, Sharma Saitowitz, extended Vos’s work at the Posthuys before going on to research the nineteenth-century Woodstock glass factory. The latter was the first venture into what would become known as industrial archaeology in South Africa.

Along with archaeologist Gabeba Abrahams-Willis’s appointment to a post at the South African Cultural History Museum during the early 1980s came her enthusiastic investigation of the potential for historical archaeology in Cape Town and her important venture into cultural resource management. Her dogged insistence that material culture relics from the colonial past be preserved for posterity astonished developers, who hitherto had been ignorant or uncaring of their value. A number of historical features have been salvaged through her efforts.

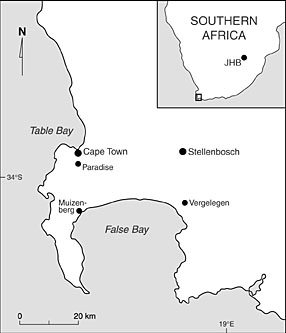

Meanwhile, from 1980 until 1983, the Department of Archaeology at the University of Cape Town was engaged in small-scale but systematic excavations at the VOC outpost of Paradijs (Paradise) in the Newlands Forest. Reports of these activities suggested a sequence of deposits at Paradijs and therefore the possibility of uncovering a succession of building phases.

It is clear that interest in the archaeology of Cape colonialism had been awakened. The gradual easing into historical archaeology received a boost in 1984 when the renowned U.S. historical archaeologist james deetz was invited to lecture at the University of Cape Town. Deetz’s inspiring lecture series on his own pioneering work in the United States coincided with Martin Hall’s decision to transfer his main interest from early–Iron Age farming communities in southern Africa to the colonial past and the impact of European expansion on the indigenous populations. Soon after his appointment as a lecturer at the University of Cape Town (where he became a full professor in 1991), Hall set about establishing historical archaeology as a subdiscipline. In the late 1980s, he gathered together interested postgraduate students to form a Historical Archaeology Research Group (HARG) and to begin the first large-scale excavations at the colonial site of Paradijs. This undertaking eventually resulted in nine seasons of fieldwork between 1985 and 1989.

Although the number of artifacts recovered was not excessive—owing, at least in part, to the situation of the site on a slope and the fact that the site was not bounded—the samples were large enough to enable comparisons with collections from other sites, and the tobacco pipe-stem count proved sufficient to be of use in working out a chronology for the various building phases. The changes in the buildings have proved to be invaluable for students interested in the development of what is generally called “Cape Dutch architecture.” The pattern of development defined after excavations at Paradijs, and interpreted as indicating a change in the mode of dwelling at the Cape during the eighteenth century, was confirmed in 1987 when a second rural dwelling complex was excavated near the town of Stellenbosch.

One of the main aims of historical archaeologists at the University of Cape Town has been to gain an understanding of the position of the underclass in Cape colonial society. Ranking was important in Europe during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and a VOC list

|  |