| Page 475 |  |

Cerveteri, a gold diadem from Perugia, and a painted archaic terracotta sarcophagus showing a couple reclining, also from Cerveteri.

Of course, the collections of the Medici and their successors, the dukes of Lorraine, were highly important. Having been assembled in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence by Luigi Lanzi, the collections were taken over by the Italian state soon after the unification of Italy in 1870. Magnificent pieces such as the Chimaera and the bronze orator (Arringatore, acquired by the Medici in 1566) were soon combined with objects recently excavated at numerous sites in Tuscany. In 1881, the Florence Archaeological Museum was established in the quarters it still occupies in the Via della Colonna. A spirited debate arose over how the material should be arranged and whether the criteria should be historical, topographical, or aesthetic. Under the direction of Luigi Milani, the Museo Topografico Centrale dell’Etruria was opened in 1897, and objects were displayed in a scientific, objective way according to their provenance and not their rank as art objects. Unfortunately, the great flood of Florence in 1966 wrecked the topographical museum, and the previous arrangement has never been regained.

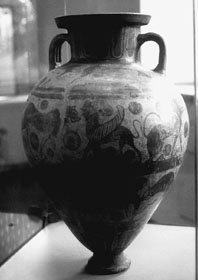

Etruscan amphora

(Ann Ronan Picture Library)

The most important collection of Etruscan-Italian antiquities in the world is that of the Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia in Rome. Instituted by decree in 1889 and housed in the historic villa of Pope Julius III (built 1551–1555), the museum was designated to house antiquities from sites in Latium in Italy. It began to function effectively in 1908 under the guidance of G.A. Colini and today boasts a successful topographical sequence of Etruscan, Faliscan, Latin, and Praenestine materials.

The question of the relationship between the Etruscans and other pre-Roman cultures became a central problem in the later nineteenth century. An acrimonious controversy arose after the discovery in 1853 at Villanova, near Bologna, of material that seemed to predate Etruscan culture as it was known at the time. “Villanovan” remains of the Italian Iron Age (1000 or 900–700 b.c.), characterized by the use of handmade ash urns and fibulae, were soon identified at other sites. Gozzadini, the owner of the land at Villanova and original discoverer of the culture (Vitali 1984), believed that Villanovan was an early phase of Etruscan civilization. He was violently opposed by Brizio and others who upheld the long-cherished theory that the Etruscans came as invaders from the east and overwhelmed native cultures (the Greek historian Herodotus had stated that the Etruscans came from Lydia in Asia Minor). Brizio was opposed not only by Gozzadini but also by Luigi Pigorini, Wolfgang Helbig, and others who argued that the Etruscans arrived in Italy from northern Europe, having come across the Alps.

The lively debates on “the origin of the Etruscans,” which had at stake nationalist pride along with various cultural and archaeological issues, led to a reexamination of existing evidence and a ferment of new ideas. In particular, scholars addressed the problem of the Etruscan language, which, they noted, defied classification with the Indo-European languages of ancient

|  |