| Page 448 |  |

cartographer) produced survey plans of the city at El Amarna that showed the basic structure of the site and several of the major ceremonial buildings in the center of the city. However, the first fully scientific study of an ancient Egyptian town, combining both survey and excavation, was Petrie’s excavation of the site of El Amarna in 1891–1892.

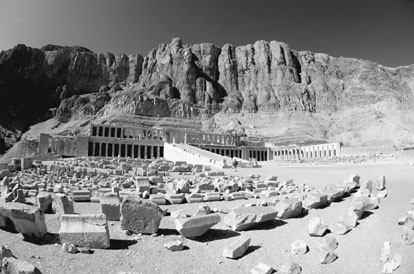

The mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut just over the cliff from the famous Valley of the Kings in Egypt

(The Purcell Team/Corbis)

In 1950 only a handful of sites could be cited as examples of Egyptian urban life: Kahun, Gurob, and El Amarna (Petrie 1890, 1891), Deir el-Medina (Bruyere 1939), and several fortified towns in nubia such as Sesebi and Amara West. These sites were all to some extent unrepresentative of Egyptian urbanization, and only the city at El Amarna was sufficiently well documented to provide any reliable archaeological basis for the analysis of Egyptian urban life. Well-preserved towns of any period were once considered to be rare in Egypt (Fairman 1949; O’Connor 1972, 683), and J.A. Wilson (1960, 24) went so far as to suggest that Egypt was “a civilization without cities.” On the few occasions when nineteenth-century and early-twentieth-century archaeologists excavated town sites (rather than simply scouring them for papyri or ostraca), which usually meant that the mud-brick walls of houses were exposed but little or no excavation took place in courtyards, streets, or other potentially significant “open” areas. Since the 1950s, however, there has been a steady increase in the available data from pharaonic urban sites. In an analysis of changing patterns in Egyptological publication, David O’Connor (1990, 241–242) points out that the percentage of published archaeological fieldwork devoted to settlements rose from 13.4 percent in 1924 to 23.2 percent in 1981. The situation, however, appears to have changed even more dramatically in the 1990s, with the 1989–1990 list of Egyptological publications showing no less than 44.4 percent of fieldwork dealing with settlement remains and a correspondingly steep decline in the excavation of nonmonumental cemeteries (see Table 1).

This growth in settlement archaeology has led to the publication of data from numerous surviving fragments of towns and villages excavated

|  |