| Page 374 |  |

countries often see the development of Latin American archaeology as having its roots in the intellectual history of that region. As Fonseca (1992, 13–15) noted (translation mine):

The archaeological tradition that has most influenced Latin America, and therefore Costa Rica, is that of North America.... [A]s inheritors of European ethnocentrism, the colonizers of North America reserved the concept of history to the study of their own origins, and the related origins of those peoples who influenced the development of their culture (in this case Native Americans).… The history of archaeology has acquired different characteristics from country to country, and from region to region. In Costa Rica, archaeologists recently began to explain our ancient history.

This tendency to identify with “our” native ancestors, and to see their remains as the roots of the national heritage, persists even though the Spanish eliminated as much as 95 percent of the indigenous population.

Furthermore, the contrasting histories of the national political systems in Nicaragua and Costa Rica have greatly impacted the development of archaeology. With longer-term stability in the university and museum systems (reflecting stability in the broader political, social, economic, and cultural dimensions of society) Costa Rica has a larger and more mature corps of archaeologists (and auxiliary museum and collaborative specialists such as botanists, chemists, etc.) than does Nicaragua.

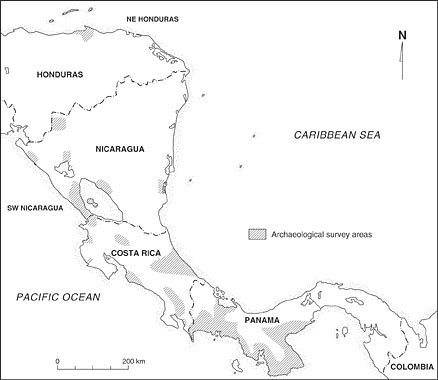

Archaeologically, this is by far the least known of the Central American republics. While there was a great deal of nineteenth century interest, and detailed summaries (Lange et al. 1992; Arellano 1993) have been written, Nicaragua is still little known, particularly in the north and east (see map).

Central American Archaeological Survey Areas

Numerous early accounts by Spanish chroniclers contain limited descriptions of gold- working, settlement patterns, subsistence practices, and religious activities. These reports were utilized by late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century researchers to speculate about external cultural contacts and influences, which were presumed to have been primarily Mesoamerican. These same data, and more recent historical overviews and secondary sources (see Radell 1969; MacCloed 1973; Newson 1987; Incer 1990) are being utilized by contemporary researchers to test models of social organization, to supplement archaeological data in the development of cultural-historical sequences, and to define patterns of localized development and regional interaction.

Ephraim G. Squier, who had been educated as an engineer, was the United States charge d’affaires to the republics of Central America during the mid-nineteenth century. He published (1852) still-important baseline data on the stone statuary and petroglyphs of Isla Zapatera and other islands in Lake Nicaragua.

Another traveler, Frederick Boyle, described the area of Chontales, and reported seeing pot-hunters destroying sites and tombs. Boyle not only wrote down his travel observations, but was also, according to Stone (1984, 25), “the first to notice the difference between the monoliths of Chontales, Niquiran, and others in Nicaragua… Boyle also illustrated Luna Ware, shoe vessels, and stone faces from Ometepe and Zapatera islands, Mombacho, and Chontales.”

|  |