| Page 335 |  |

Iron Age seasonal occupations. During World War II he traveled to Kenya, Ethiopia, British Somaliland, and Madagascar, where he renewed his friendship with louis and mary leakey. The results of these travels, the material he collected, and the sites he surveyed were the basis of his highly respected book Prehistoric Cultures of the Horn of Africa (1954).

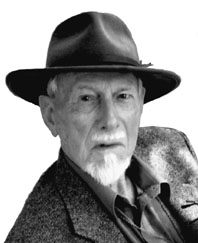

J. Desmond Clark

(H. J. Deacon)

In 1947, Louis Leakey organized and hosted the First Pan-African Congress on Prehistory, and it brought together for the first time almost everyone interested in African prehistory—archaeologists, quaternary geologists, and paleontologists from twenty-six countries and from all parts of Africa and abroad. The congress gave those who attended the opportunity to meet and learn what others were doing and to discuss mutual problems. It was a landmark event for African prehistory and for Clark. Over the next decade he worked in the upper Zambezi Valley, dug the late–Stone Age cave of Nachikufu, and reexamined the Broken Hill site where the “Rhodesian man” had been found in 1921. He took leave and returned to Cambridge where he received his doctorate in 1951, writing his thesis on his work in the Zambezi Valley and the Horn of Africa.

The Second Pan-African Congress was held in 1952 in Algiers, and Clark was president of the prehistory section. Stimulated by the congress papers and collections, Clark proposed a correlation of prehistoric cultures north and south of the Sahara. Although the model he proposed is now known to be incorrect, it was Clark’s first attempt to view African prehistory as a whole. In 1953, Clark found the most important site of his career at Kalambo Falls in Northern Rhodesia, and the publication of his research there established him as one of the two leading African prehistorians—the other being Louis Leakey. Clark assembled a diverse group of scholars and used a multidisciplinary approach to reconstruct the paleoenvironments of the site. A number of students and young scholars, including many who are now major figures in prehistoric studies in Africa and elsewhere, participated in the excavation and the writing of the reports.

During the 1950s, Clark published forty-six papers in addition to the proceedings of the Third Pan-African Congress held in 1955 in Livingstone and his synthesis, the Prehistory of Southern Africa. He continued to excavate in Angola and in the Zambezi Valley. In 1961, he became a professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of California at Berkeley, and there he and other colleagues established a research and graduate-training program in African prehistory and related disciplines that soon became the most distinguished center for such studies in the world. By the time Clark retired from teaching in 1986, ten Africans from six different countries had received their doctorates under his direction. These African graduates are now university teachers, museum directors, and heads of antiquities organizations in their own countries. During this period Clark also expanded his research interests to Malawi, the central Sahara, central Sudan, and Ethiopia.

The breadth of Clark’s personal experience in African prehistory is unique, not only because of the range of the areas he has studied but also because of the diversity of topics and their chronological range. His greatest contribution has been his ability to place the mass of data in its broader

|  |