| Page 322 |  |

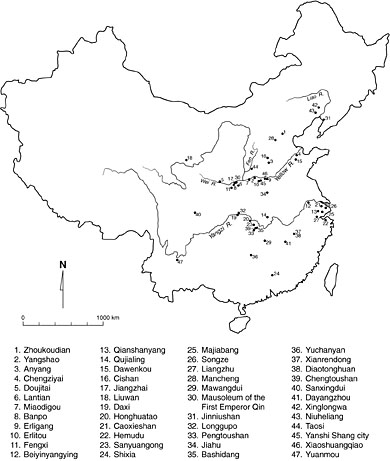

of this evolutionary scheme in archaeology was the analysis of a Yangshao site at Banpo near Xi’an, Shaanxi Province. The excavations, led by Shi Xingbang, revealed a large portion of a Yangshao settlement. Based on burials and residential patterns, the Banpo Neolithic village was described as a matrilineal society in which women enjoyed high social status and in which “pairing marriage” was practiced (Institute of Archaeology, Academia Sinica 1963). Such statements soon became standard in many interpretations of Neolithic sites dating to the Yangshao period, and the classic evolutionary model was commonly accepted among Chinese archaeologists.

Shang archaeology was still a focus of research. Anyang resumed its importance as a center of archaeological excavations and yielded royal tombs, sacrificial pits, craft workshops, and inscribed oracle bones. These finds enriched the understanding of the spatial organization of the site (Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences 1994). In the early 1950s, Shang material remains that could be dated to a period earlier than Anyang were first recognized at Erligang, near Zhengzhou, Henan Province. A fortified Shang city belonging to the Erligang phase was then found at Zhengzhou. The enormous size of the rammed-earth enclosure (300 hectares in area) and abundant remains found at the site (craft workshops, palace foundations, and elite burials) indicated that it may have been a capital city before Anyang (Henan Bureau of Cultural Relics 1959). This discovery encouraged archaeologists to search for the earliest remains of the Xia and Shang dynasties.

Inspired by ancient textual records, Xu Xusheng led a survey team in western Henan Province to explore the remains of the Xia dynasty. His endeavor soon proved fruitful when the team discovered a large Bronze Age site at Erlitou in Yanshi (Xu 1959). The Erlitou site was dated earlier than the Erligang phase, and subsequent excavations yielded a large palatial foundation, indicating the high rank of the site. The site was then designated as the type site of the Erlitou culture, which preceded the Erligang phase of the Shang (Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences 1999).

The discovery of Erligang and Erlitou generated considerable debate on many issues: whether Erlitou was a capital city of the Xia or the Shang, which phases of the Erlitou culture belong to the Xia or the Shang cultures, and which capital cities named in ancient texts corresponded to Erligang and Erlitou. Most arguments were made on the basis of textual records that were written thousand of years after the existence of the Xia and Shang and reinterpreted by many individuals afterward. As people used different textual sources, which frequently contradicted one another to support their opinions, these debates have continued for decades without reaching a consensus (Dong 1999).

Between the mid-1950s and early 1960s, excavations at Fengxi, Chang’an, Shaanxi Province, revealed a large Bronze Age site, and it was determined that the site was the location of the capital cities of the western Zhou: Feng and Hao. These finds established the cultural sequence and chronology of the Zhou archaeological record (Institute of Archaeology, Academia Sinica 1962).

Bronze ritual vessel of the Shang period, twelfth century B.C.

(Image Select)

Archaeological research during this period primarily focused on the central plains of the Yellow River valley, where a clear sequence of cultural development could be traced from the Yangshao to the Longshan to the three dynasties.

|  |