| Page 268 |  |

peoples and cultures, as the original title of their congresses indicates. They have defined each people by its culture and each culture by its material remains and have worked back from the cultures of the historic ethnic groups to those of the prehistoric peoples, using the so-called direct historical method.

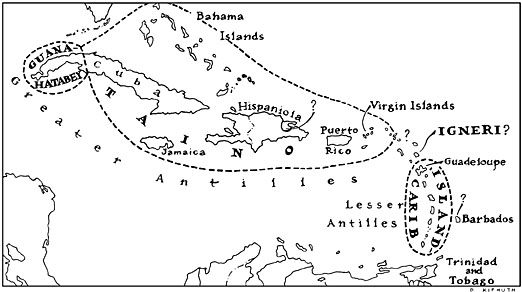

Map 3. Ethnic Groups in the West Indies at the Time of Columbus

(after Rouse 1994, Fig. 1)

They have approached this task by assuming that in the absence of evidence to the contrary, the inhabitants of each local period constituted a separate people, with its own distinctive culture. Since local peoples and cultures are too small to be directly equated with the ethnic groups, they have had to be grouped into larger units for the purpose of correlation. In other words, they have had to be organized into cultural taxonomies.

Cruxent and Rouse (1958–1959) formed such a taxonomy while constructing regional chronologies in Venezuela. During the course of that research they tested the alignment of the local periods in their charts by studying the distributions of single traits and complexes of traits. They applied the term horizon or the phrase horizon style to the traits or complexes that had a horizontal distribution and referred to the traits and complexes that had irregular distributions as traditions, following the example of Willey (1945).

They also began to pay attention to the totality of traits present within each period, that is, to the periods’ cultures. They assigned the cultures that looked alike to separate classes regardless of their chronological position. They considered calling these classes of cultures traditions, because they are irregularly distributed on the charts, but rejected that idea because it might cause their research on the history of classes of cultures to be confused with their study of the history of classes of artifacts and features, that is, of cultural traits. They decided to call the classes into which they had grouped their cultures series and to limit their use of the word tradition to classes of artifacts and features, defined by their types and modes, respectively. Other Caribbeanists have preferred to apply tradition indiscriminately to both kinds of units.

Rouse (1964) introduced the concept of series or whole-culture traditions into the West Indies, and it has been almost universally adopted there. Vescelius (1986) subsequently proposed that each series be divided into subseries, which has been done throughout the West Indies but not so widely on the mainland. Each series has been named by adding the suffix -oid to the name of a period in which it occurred, and each subseries has been named by substituting the suffix -an. As elsewhere (see, e.g., Lumbreras 1974), these suffixes

|  |