| Page 266 |  |

Ripley P. Bullen (1964) pioneered the development of local sequences for the Windward Islands in the southern half of the Lesser Antilles, and Louis Allaire (1973) synthesized them into another regional chronology, which he has been modifying and expanding as new data have become available. Only two peripheral groups of relatively small islands still lack adequate chronological control, the Leewards between the Windwards and the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas north of the latter. Local sequences of periods are currently being formulated for both these regions (e.g., Berman and Gnivecki 1994; Hofman 1993).

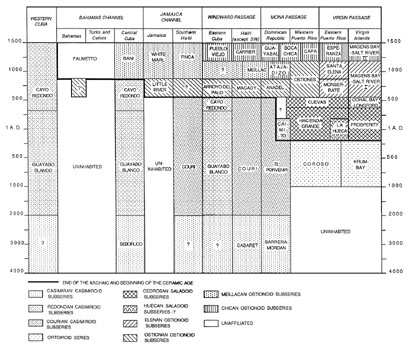

Figure 2. Chronology of the Greater Antilles

(after Rouse 1992, Figure 14)

Chronological research has also spread to the mainland part of the Caribbean area but has not been so systematically done there. In 1946, Rouse worked out a sequence of periods for the island of Trinidad, just off the mouth of the Orinoco River, in collaboration with J.A. Bullbrook, an oil geologist with previous archaeological experience in the Sudan (Bullbrook 1953; Rouse 1947). In 1950, Professor José M. Cruxent invited Rouse to join him in establishing a regional chronology for Venezuela (Cruxent and Rouse 1958–1959). The results of both projects have been refined and expanded by subsequent investigators (Barse 1989; Gassón and Wagner 1991; Sanoja and Vargas 1983). Sequences of local periods have also been constructed for Guyana by Evans and Meggers (1960) and for the former Dutch colonies by archaeologists from that country (e.g., Versteeg and Bubberman 1992). Only in French Guiana has archaeology not yet advanced beyond the stage of artifactual research.

The introduction of radiometric dating in the 1950s led to a temporary decline of interest in