| Page 249 |  |

of significant families and knowledgeable about the office and ceremonies of state. He became the historian of his own age, writing an important account of the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I, so that by the end of his own life he was not only the master of British antiquity but also the interpreter of the modern political scene.

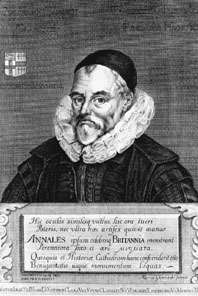

William Camden

(Hulton Getty)

Britannia broke with the mythologies of British history by taking advantage of the existence of a wide range of well-edited classical texts, the product of a century of humanist scholarship. Camden was persuaded that the people who occupied Britain at the time of the Roman invasions were closely related to the Gauls, whom he was able to identify as a Celtic people. He also examined the origins of the Picts and the Scots. To solve problems of origins and relationships, Camden employed etymology. Already proficient in Greek and Latin, he learned Welsh and studied Anglo-Saxon. He was also particularly attentive to the coinage of the Britons in the first century a.d. But it was the relating of history to landscape that was the permanent achievement of Britiannia. The body of the book took the form of a “perambulation” through the counties of Britain, with Camden offering a many-layered account of each particular region. Camden made a number of field trips to examine monuments and to gather information—he saw more of Britain at first hand than any previous observer.

Six editions of Britannia were published between 1586 and 1607, an English translation appeared in 1610 and 1637, and another Latin edition was published in Frankfurt in 1590. The appearance of Britannia in 1586 might well have prompted the formation of the society of antiquaries of london, which began to meet in that year. It certainly encouraged the growth of antiquarian studies in provincial centers by stimulating local curiosity about the regional past.

Camden enjoyed the friendship of a wide circle of European humanist scholars, such as Scaliger, Ortelius, Lipsius, Hondius, Casaubon, Peiresc, Hotman, and de Thou. Largely through his contacts, English antiquaries of the Jacobean age were linked to their European counterparts.

References

For references, see Encyclopedia of Archaeology: The Great Archaeologists, Vol. 1, ed. Tim Murray (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 1999), p. 13.

The border between Canada and the United States slices arbitrarily across North America, and European colonization began north of the border almost as early as to the south. Yet, for climatic and geological reasons, European settlement progressed more slowly in Canada, and the bulk of the country’s population remained concentrated near the border. The surface area of Canada is larger than that of the United States, but Canada is only about one-tenth as populous. Because of this and related political factors, archaeology has developed in Canada more slowly and somewhat differently than it has in the United States.

|  |