| Page 174 |  |

Interaction in the Cinty Valley, Chuquisaca, Bolivia.” Unpublished paper presented to the sixty-third annual meeting of the Society of American Archaeology, Seattle, Washington.

Rivera Sundt, Oswaldo. 1989. Resultados de la excavación en el centro ceremonial de lukurmata. Vol. 2, Arqueología de Lukurmata. La Paz: Producciones Puma Punku.

Rydén, Stig. 1952. “Chullpa Pampa: A Pre-Tihuanacu Archaeological Site in the Cochabamba Region, a Preliminary Report.” Ethnos 1–4: 39–50.

———. 1957. Andean Excavations, I: The Tihuanaco Era East of Lake Titicaca. Monograph series. Stockholm: Ethnographical Museum of Sweden.

Sampeck, Kathryn E. 1991. “Excavations at Putuni, Tiwanaku, Bolivia.” M.A. thesis, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Chicago.

Squier, E. George. 1870. “The Primeval Monuments of Peru Compared with Those in Other Parts of the World.” American Naturalist 4: 3–19.

Stanish, Charles, Brian Bauer, Oswaldo River, Javier Escalante, and Matt Seddon. 1996. “Report of Proyecto tiksi Kjarka on the Island of the Sun, Bolivia, 1994–1995.” Unpublished document.

Sutherland, Cheryl Ann. 1991. “Methodological Stylistic and Functional Ceramic Analysis: The Surface Collection at Akapana-East Tiwanaku.” M.A. thesis, Department of Anthropology, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Chicago.

Tschudi, Johan J. 1963. Peru: Reiseskizzen aus den Jahren 1838–1842. Graz: Akademische Druck.

Walter, Heinz. 1968. Archäologische Studien in den Kordilleren Boliviens II: Beitrage zur Archäologie Boliviens. Baessler-Archiv, Beitrage zur volkerkunde. Berlin: Verlag Von Dietrich Reimer.

Webster, Ann DeMuth. 1993. “The Role of South American Camelid in the Development of the Tiwanaku State.” Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Chicago.

A classic Maya site in Chiapas in southern mexico, Bonampak’ is most famous for the well-preserved murals adorning the interior walls of its principal temple. For decades the temple had been a place of worship by the Lacandon Maya, who today inhabit the region, but the murals became known to the outside world only in 1946.

Bonampak’ was the capital city of one of the many small kingdoms that formed the map of the Maya world during the Maya classic period (a.d. 250–900). It alternated between peaceful and bellicose relations with its neighbors, and like many other kingdoms during the classic period was at times dominant and at other times subservient in the hierarchy of kingdoms in the complex political geography of the times. The most famous king of Bonampak’ was Yajaw-Chan-Muwa:n, who was responsible for most of the carved monuments that survive at the site. Yajaw-Chan-Muwa:n, who was related by marriage to the royal family of Yaxchilan that lived in a neighboring kingdom, became king of Bonampak’ in a.d. 776, toward the end of the capital’s history. In one of his carved stelae (Bonampak’ Stela 2), he portrays himself about to let blood from his genitals, flanked by his wife (a princess of Yaxchilan) and his mother.

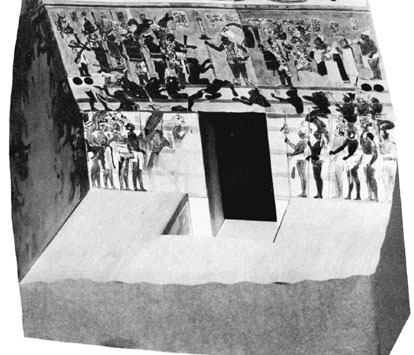

Yajaw-Chan-Muwa:n also built and decorated Structure 1 of Bonampak’, which contains the famous murals. These murals are among the best preserved in Mesoamerica and give a fascinating glimpse into classic Maya ritual, warfare, and courtly life. The murals cover the surfaces of all three rooms of the temple. The first room portrays an elaborate procession at the Bonampak’ court, in which the key event is the public presentation of the young son of Yajaw-Chan-Muwa:n as the heir apparent to the throne of the kingdom. In the second room is the depiction of a pitched battle in which Yajaw-Chan-Muwa:n and his allies are victorious. Over the doorway of this room, the captives—destined for sacrifice—are displayed before Yajaw-Chan-Muwa:n. The murals in the third room show the victory dance of the triumphant Bonampak’ lords while a captive is being sacrificed and members of the court are engaged in letting their own blood.

A view from the back, toward the entrance, Temple of Murals, Bonampak’

(Ann Ronan Picture Library)

These wonderful murals were intended to be a lasting record of the ceremonies surrounding the designation of Yajaw-Chan-Muwa:n’s son as heir to the throne. The irony is that the young boy portrayed in the murals almost certainly never became king, for, apparently, the site was abandoned before he ever came of age, and

|  |