| Page 166 |  |

human races in South America; Johan J. Tschudi (1851), a German naturalist who described the early native monuments around 1838–1842; and Francis de Castelnau (1851), who argued that Tiwanaku was an influential predecessor of the Inca empire. Ephraim George Squier (1870), a U.S. diplomat appointed to Lima, peru, in the 1860s, stands out for his detailed description and mapping of Tiwanaku and other important archaeological sites (Albarracín-Jordan 1999; Ponce Sanginés 1995).

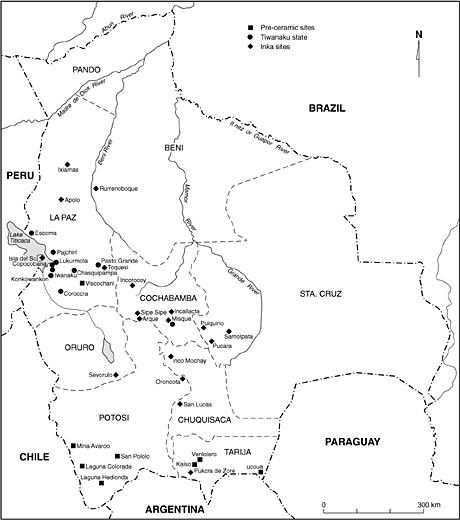

Bolivian Archaeological Sites

On the local level, the consolidation of Bolivia as a nation state was coupled with the need of emerging Creole elites to develop their own sense of identity, one that was different from that of colonial Spain but still divorced from the oppressed Indian populations. Additionally, the increasing visits of foreign explorers involved with diplomatic affairs renewed the interest of the Bolivian government in its ancient monuments. For example, the Bolivian president José Ballivian ordered nonsystematic excavations in Tiwanaku with only the goal of collecting archaeological pieces for the local museum in the city of La Paz (Ponce Sanginés 1995). The perception that archaeology was simply part of art history, involved with the recollection and collection of aesthetic artifacts, was part of a broader tendency in the first stages of archaeology before its consolidation as a science. During this period, and even later, most of the archaeological work in Bolivia was restricted to the collection of artifacts and description of archaeological monuments.

During the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth, the beginnings of Bolivian archaeology emerged with a more scientific approach. These first efforts were by foreign researchers visiting Bolivia, most of them part of research programs promoted by international museums. The goal of these scholars was, not just scientific inquiry, but in some cases, to acquire archaeological collections for exhibition in foreign museums. This practice of acquiring collections of artifacts from developing countries for display in the home country’s museums was part of the colonial approach to archaeology and typical of those times. On a national level, this was the period of intensive exploitation and export of tin and the advent of liberalism and modernism into the Bolivian political arena.

Adolph Bandelier, an archaeologist working in the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, visited different places in Peru and Bolivia during 1892–1897. From Bolivia, Bandelier (1910) provided important descriptions, maps, and collected indigenous myths of origin from the Island of the Sun, the Island of the Moon, and Tiwanaku (the mythical centers of origin of the Inca empire). He also collected archaeological objects that were later transported to the American Museum of Natural History.

Erland Nordenskiöld, a Swedish scholar, also conducted several scientific expeditions with an archaeological and ethnographical focus in different areas of Bolivian territory during 1901–1914. His work was conducted not only in the Bolivian highlands, but he was also one of the first to provide firsthand information about the intermediate valleys and Amazonian tropics. He described the variety of ethnic groups inhabiting those areas, and he also carried out excavations at several habitation mounds in the lowlands (Trinidad), at sites located in the valleys of Cochabamba (Mizque, Caballero, Saipina), and in Santa Cruz. He provided the first relative chronologies and detailed artifact inventories, and he identified previously unknown archaeological cultures. His extensive work was published in 1953.

The work of Arthur Posnansky (1904–1940) also stands out. As a naval engineer from Vienna who was impressed by the ruins of Tiwanaku, Posnansky (1945) produced detailed maps of the monuments and structures in Tiwanaku. He also speculated that this ancient culture was the cradle of American humans and that Tiwanaku was on the shores of an ancient lake.

In 1903, a multidisciplinary French expedition directed by Georges de Crèqui-Montfort made the first excavations in Tiwanaku. Several areas of Tiwanaku were excavated such as the pyramid of Akapana, the semi-sunken temple of

|  |