| Page 143 |  |

using archaeological evidence relating to the late-protohistoric and early-historic periods. Although occasional chance discoveries had been made in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, e.g., the tomb of the Merovingian king Childeric at Tournai in 1653 and the Celtic burial chamber at Eigenbilzen in 1781, an incipient archaeological interest emerged in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Such activities were stimulated by the Imperial Academy of Brussels and later by the Royal Academy, which was founded in 1816 during the short-lived reign of the Dutch king William I.

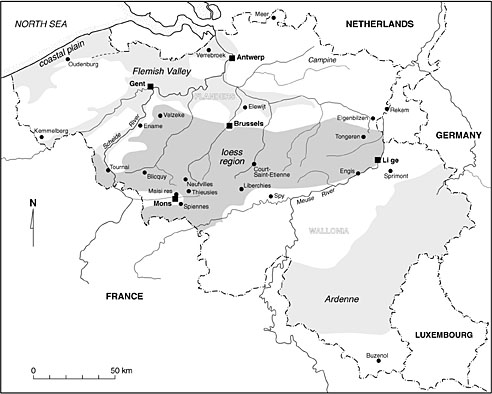

Archaeological Sites in Belgium

The name Belgium came from the Roman province of Belgica, which was established in northern Gaul after Julius Caesar’s conquest in 59–52 b.c. It was divided into a number of civitates (regions) inhabited by the Belgae, a people of Germano-Celtic origin who had crossed the Rhine in the last centuries b.c. Early historians such as Caussin, De Bast, Dewez, and Heylen (writing in Latin) were interested in tribal territories, their main centers, and the Celtic origin of modern cities. Problems like these were addressed using such evidence as the distribution of coin treasures. Tongeren, capital of the Civitas Tungrorum and Belgium’s main Roman center, received particular attention.

In the years after 1830, nationalist motives made archaeology a recognized discipline. It figured as an independent section within the Class of Letters of the Royal Academy, and in 1835, it was among the obligatory fields of instruction at the four universities. Private historical and archaeological societies were also established. The most important of these were the Royal Academy of Archaeology at Antwerp and the Archaeological Society of Brussels. Most fieldwork was done by members of the societies, who were often members of the clergy or nobility. The historic roots of the different language groups, or “races” in the current terminology,

|  |