| Page 1241 |  |

“lakeshore Neolithic” (Vouga 1923). Several other lake-dwelling excavations were undertaken in Switzerland at the same time, but it was in Germany that fundamental objections to the basis of the lake-dwelling theory were to originate. In 1926, German archaeologist Hans Reinerth argued that palafittic lake villages, while laid out on platforms, were set back from the water on lakeshores whose levels must have been lower (Reinerth 1926). Later archaeologists went even further and argued that, in fact, lake dwellings had always been situated on dry land.

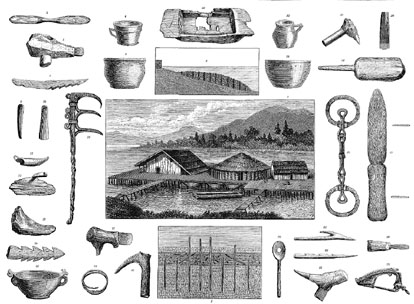

Artist’s rendition of lake dwellings and associated artifacts. In the early twentieth century reinterpretation of the archaeological evidence suggested that the dwellings had been constructed on dry land.

(Ann Ronan Picture Library)

From then on the debate became impassioned, with Swiss scientists unable to question what had become a sacred national myth. At the same time, because of the Nazi Party’s rise to power, Switzerland was trying to protect itself against the designs of Grossdeutschland (the view that all German speakers should be in one country) and claims for the incorporation of “Germanic” territories. Swiss archaeologists clung to the image of their country as a cultural unity from prehistoric times. The background ideological debate assumed even greater importance because Reinerth, beginning in 1932, ran the Prehistory Service of the Nazi Party. In the long term, the debate proved useless, with neither side having the necessary evidence to substantiate a scientific solution. Nonetheless, the impetus to reexamine palafittic building methods was owing to the German archaeologists. Because of the political context, however, these new approaches began to have a further impact only after World War II.

The debate, passionate among archaeologists, made hardly any impact on the rest of the population. Since the end of the nineteenth century, archaeological studies had ceased to engender popular enthusiasm, and archaeologists working during the first part of the twentieth century in Switzerland lacked charisma or any interest in popularizing their research. More importantly, they also lacked direction. Culture-historical archaeology was popular in the rest of contemporary

|  |