| Page 1092 |  |

Although this approach to archaeology had dire consequences and many limitations, it also resulted in some interesting interpretations and directions within the discipline. Because Russian archaeologists had to concentrate on how ordinary people lived, they undertook large-scale excavations of settlements, camps, and work sites and therefore collected important data in the areas of Paleolithic and Neolithic houses and settlements in particular.

See also

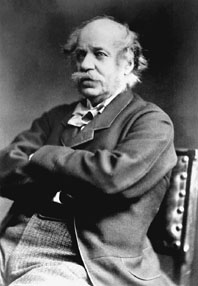

(1810–1895)

Henry Creswicke Rawlinson was born in England the son of wealthy middle-class parents. He took up a military cadetship in the East India Company in 1827 and while serving in that capacity met the governor of India, Sir John Malcolm, a diplomat and oriental scholar who inspired and encouraged the young Rawlinson’s prodigious interest in languages. In 1839, he was sent to Persia (now iran) to help reorganize the Persian army by raising regiments from frontier tribes in order to prevent the spread of Russian influence toward India. Also in 1839, he helped with the crisis in Afghanistan, becoming a British political agent in Kandahar where he raised Persian cavalry that fought in subsequent battles with the Afghanis.

Henry Creswicke Rawlinson

(Hulton Getty)

Rawlinson continued to study throughout his military career, and his language and leadership abilities were so exceptional that he was appointed to explore unknown areas of the subcontinent, central Asia, and the Middle East. These included Susiana (now southwestern Iran) in 1836, and in 1838 he explored Persian Kurdistan for the Royal Geographic Society, for which he was awarded the society’s gold medal. It was during this trip that he first became interested in cuneiform inscriptions. In 1843, Rawlinson became a political agent for the East India Company in Turkish Arabia, as well as becoming a British consul in Baghdad, and combined his new interests in epigraphy and archaeology with his diplomatic career.

He began to locate and copy, decipher, and translate Persian cuneiform inscriptions and to publish them in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. At the same time that he was working in Iraq and Iran, several other scholars of philology in England and Ireland were endeavoring to decipher cuneiform from the direction of its vowel systems. All of the independent translators, including Rawlinson, were given an undeciphered inscription to test their ability. The results so closely resembled each other that cuneiform was officially recognized as deciphered—an epigraphic triumph similar to that by the great French philologist jean-françois champollion in the field of Egyptian hieroglyphics. But it was Rawlinson’s translations of inscriptions “in the field” that were the most important contribution—and earned him the title of the first successful decipherer of cuneiform.

Rawlinson returned to England in 1849 and was commissioned by the british museum to excavate in Babylonia for the benefit of that institution’s collections. In 1851, Rawlinson was asked by the British Museum to revise the second

|  |