| Page 1086 |  |

Likewise, theories of race had an important impact on the development of archaeological theory and method. Human remains from archaeological sites provided evidence for the definition of racial types on the basis of metric analyses of skeletal components. In the European context the most common mode of racial classification was based on measurements of the shape and size of the skull, and the distinction between the dolichocephalic (longheaded) northern races and the brachycephalic (roundheaded) southern races became particularly significant in debates about European prehistory. Human skeletal remains were especially important sources of evidence in debates concerning the longevity of specific races and disputes about the permanence or fluidity of racial traits and groups.

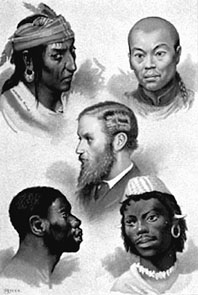

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752–1840) is often called the father of physical anthropology and the first to develop a scientific concept of race. He divided the human race into five types: Caucasian, Mongolian, Malay, Ethiopian, and American.

(Image Select)

Archaeologists, for their part, often used direct associations between material culture and skeletal material as the basis for the attribution of racial categories to specific archaeological cultures. However, the widespread claim that cultural capabilities were directly tied to racial heritage meant that archaeologists could apply racial attributions to their evidence even in the absence of skeletal remains. During the late nineteenth century broad similarities in forms of technology, subsistence, architecture, and art were used as means of distinguishing the so-called lower and higher races according to an evolutionary scale ranging from savagery through barbarism to civilization. There was little concern with the history of particular racial groups; rather, the focus was on the establishment of a universal history of race through the comparative study of both ethnographic and archaeological material culture. Good examples of such an approach can be found in the work of Gen. augustus pitt rivers (see, for instance, The Evolution of Culture [J. L. Myres, ed., 1906]) and John Lubbock (lord avebury)(see, for instance, Pre-historic Times [1865]). For a recent overview of such work, see Bruce Trigger’s A History of Archaeological Thought (1989).

By the early twentieth century the emphasis in both archaeological and anthropological research was starting to shift away from an overarching concern with social evolution and toward an interest in the particularistic histories of specific racial groups. Strong resemblances between material culture assemblages were regarded as de facto evidence for a shared racial heritage or, as it was often phrased, an “affinity of blood.” One of the forerunners of this approach in Europe was the German scholar gustaf kossinna, who developed and applied the method of “settlement archaeology.” His approach was based on the axiom that sharply delineated archaeological culture areas coincide with clearly recognizable peoples largely conceived of in racial terms. To trace the history of present-day racial groups, he argued for a retrospective approach whereby the historically attested settlement of a specific group could be traced back into prehistory on the basis of a continuity in associated styles of material culture. Historical linguistics also provided an important source of evidence, as race, language, and culture were assumed to be

|  |