Đối tác chính thức của fb88 tặng 100k

FB88 | Nhà cái xanh chín dành cho những anh em đam mê game

FB88 được biết đến là sân chơi cá cược thể thao uy tín và đẳng cấp nhất trên thị trường cá cược trực tuyến hiện nay. Tại đây, anh em được thỏa sức tham gia vào các trò chơi thú vị và hấp dẫn. Bên cạnh giá trị tiền thưởng cực kỳ hậu hĩnh, cổng game còn liên tục cập nhật những tính năng mới nhằm tăng trải nghiệm của người chơi. Bài viết dưới đây sẽ giới thiệu chi tiết về FB88 giúp anh em game thủ có cái nhìn tổng quan hơn về sân chơi này.

Tổng quan về nhà cái FB88

Nếu là một người đam mê với bộ môn cá cược ăn tiền trực tuyến thì chắc hẳn FB88 đã không còn xa lạ gì với anh em. Sân chơi này chính thức ra mắt người chơi vào năm 2016 và có trụ sở chính tại Philippines. FB88 đã nhanh chóng chiếm lĩnh thị trường cá cược tại các nước châu Á với số lượng thành viên đăng ký hùng hậu.

Cổng game đã tạo dựng được niềm tin với người chơi khi được cấp giấy phép hoạt động của hàng loạt cơ quan, tổ chức có thẩm quyền như: First Cagayan Leisure & Resort Corporation và Cagayan Economic Zone Authority (CEZA). Vì thế, khi bước vào cổng game FB88, các hoạt động cá cược đều đảm bảo công bằng, minh bạch tuyệt đối. Game thủ hoàn toàn yên tâm về tính pháp lý khi tham gia các trò chơi tại cổng game.

Một số tựa game được săn đón nhất tại cổng game FB88

FB88 là một trang web cung cấp đa dạng các tựa game cá cược được nhiều anh em cược thủ tham gia mỗi ngày. Khi truy cập vào nhà cái, bet thủ dễ dàng được trải nghiệm vô số các sản phẩm chất lượng với tỷ lệ kèo cược hấp dẫn. Sau đây là một số tựa game của sân chơi FB88 được yêu thích nhất.

Bắn cá

Nhắc đến cổng game bài đổi thưởng FB88 không thể bỏ qua sảnh cược bắn cá trực tuyến với thiết kế đồ họa 3D siêu chân thực. Ngoài ra, hệ thống âm thanh trong trò chơi cũng được đầu tư kỹ lưỡng cùng hàng loạt các tính năng hiện đại, mới mẻ. Khi bước vào bắn cá FB88, người chơi như được hóa thân thành một ngư thủ đang khám phá một đại dương bao la và được trải nghiệm cảm giác săn cá đỉnh cao. Hơn nữa, khi bắn hạ các loài sinh vật biển bạn còn được rinh về những phần thưởng giá trị.

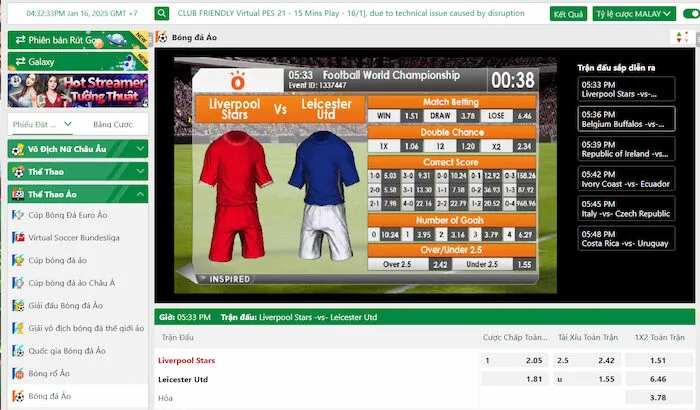

Thể thao ảo

Thể thao ảo là sảnh cược nổi tiếng tại FB88 mang đến cho người chơi những trận đấu đầy kịch tính. Điểm đặc biệt của các trò chơi sảnh cược này đó chính là tỷ lệ kèo cực kỳ hấp dẫn. Người chơi có thể thoải mái lựa chọn trò chơi mà mình yêu thích với tỷ lệ trúng thưởng cao.

Cá cược thể thao

Cá cược thể thao là sân chơi “đắt khách” nhất với bảng tỷ lệ kèo cập nhật sớm kết hợp với tiện ích soi kèo. Tại đây, gamer được thưởng thức trọn vẹn thế giới cá cược thể thao với những trò chơi độc đáo như: Thể thao 3, Thể thao 5, Thể thao 7, Thể thao 247.

Ngoài ra, hệ thống nhà cái FB88 còn thường xuyên cập nhật các giải đấu với quy mô lớn nhỏ trên toàn thế giới như: giải Cúp C1, C2, giải Ngoại Hạng Anh, Champions League, World Cup,… Các tỷ lệ kèo cược rất đa dạng và chất lượng có thể kể đến như: kèo châu Âu, kèo tài xỉu, phạt góc, chẵn lẻ, tỉ số,…Hội viên có thể tham gia vào dự đoán trận đấu, cá cược trực tiếp hoặc theo dõi ngay khi trận đấu đang diễn ra. Tỷ lệ kèo được công bố minh bạch và cạnh tranh nhất.

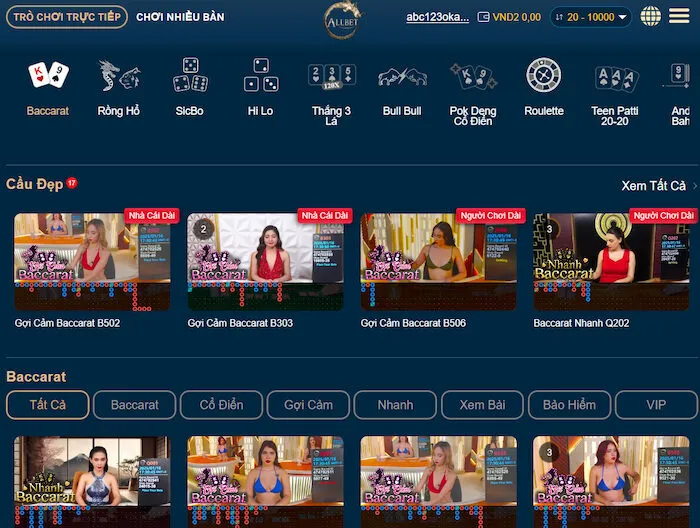

Casino trực tuyến

Không hổ danh là nhà cái đẳng cấp nhất, hiện tại FB88 đang cung cấp nhiều trò chơi casino hấp dẫn không khác gì tại những sòng bạc châu Âu với số lượng lớn người chơi tham gia. Tất cả các trò chơi sòng bài trực tuyến siêu hot đều quy tụ tại đây như: Xóc đĩa, Tài xỉu, Roulette, Phỏm, Mậu binh, Fantan, Baccarat,… Ở mỗi trò chơi đều được xây dựng lối chơi thân thiện và luật lệ đơn giản. Hơn nữa tất cả các hoạt động liên quan đến cá cược đều được phát sóng trực tiếp đảm bảo công bằng tuyệt đối. Người chơi còn có cơ hội tương tác trực tiếp với các dealer xinh đẹp và giàu kinh nghiệm mang lại trải nghiệm giải trí đỉnh cao.

Xổ số

Nếu là người có niềm đam mê với các con số thì xổ số FB88 sẽ không làm anh em thất vọng. Điểm ấn tượng của sân chơi này chính là mọi chi tiết từ hình ảnh cho đến âm thanh đều được chọn lọc kỹ càng và thiết kế bố cục có tính logic cao.

Nền tảng đã triển khai hàng loạt phiên bản đỉnh cao như: lô đề, keno và quay số siêu tốc với thời gian quay thưởng linh hoạt. Gamer có thể đặt cược với số vốn nhỏ nhưng vẫn có cơ hội trúng thưởng lớn.

Quay hũ

FB88 cung cấp nhiều trò chơi quay hũ đình đám mà anh em nên khám phá. Những siêu phẩm đều được xây dựng từ các nhà phát triển hàng đầu như Microgaming, Playtech hay JILI. Những chủ đề trong game đa dạng hứa hẹn sẽ mang đến sự hài lòng và trải nghiệm săn Jackpot trọn vẹn cho anh em bet thủ. Cổng game đảm bảo mang đến trải nghiệm săn hũ lành mạnh, văn minh và công bằng. Ngoài ra, FB88 còn trang bị nhiều tính năng độc đáo đem đến những giây phút giải trí vui vẻ, phấn khích.

Esports

Nếu người chơi có niềm đam mê với thể loại game đầy hồi hộp, gay cấn thì hãy trải nghiệm với Esports FB88. Sảnh cược đem đến cho bet thủ những phút giây giải trí đỉnh cao với hàng loạt trò chơi thể thao điện tử hot nhất hiện nay. Khi đặt cược Esports tại nhà cái, bạn không chỉ được hòa mình vào không khí sôi động của những giải đấu hot nhất mà còn được rinh tiền thưởng hấp dẫn.

Đánh giá chuẩn xác về cổng game bài đổi thưởng FB88

Không phải ngẫu nhiên mà cổng game FB88 được tìm kiếm và thu hút hàng nghìn lượt truy cập mỗi ngày. Sau đây là những ưu điểm nổi bật của sân chơi cá cược này:

Giao diện bắt mắt

Thiết kế giao diện cổng game FB88 được giới chuyên gia đánh giá rất cao. Tất cả các danh mục trên hệ thống đều được phân chia rõ ràng, thông tin đầy đủ giúp người chơi truy cập và tìm kiếm dễ dàng, nhanh chóng. Bên cạnh đó, cổng game còn sử dụng hình ảnh tinh tế, hệ thống âm thanh sống động mang đến cho người chơi những trải nghiệm đặt cược chân thực và thú vị nhất.

Chất lượng dịch vụ hàng đầu

Bên cạnh hệ thống cá cược, các dịch vụ dành cho người chơi tại FB88 cũng được nâng cấp và bảo trì. Tất cả các trải nghiệm đều mượt mà và trơn tru. Bên cạnh đó, hệ thống nhà cái luôn được nâng cấp với các dịch vụ và tính năng mới. Người chơi dễ dàng thao tác và tham gia chơi cá cược tiện lợi và nhanh chóng hơn.

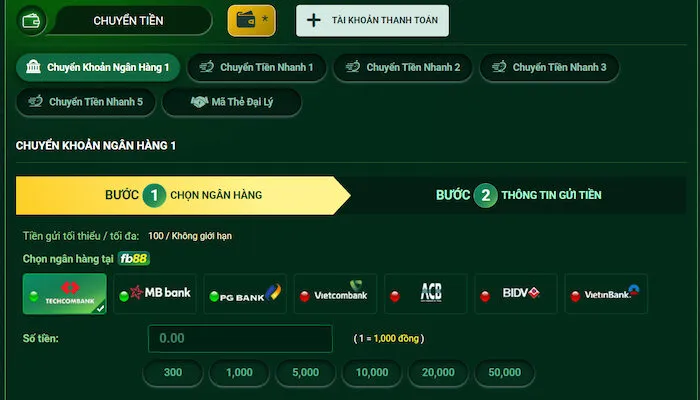

Rút – nạp tiền nhanh chóng, tiện lợi

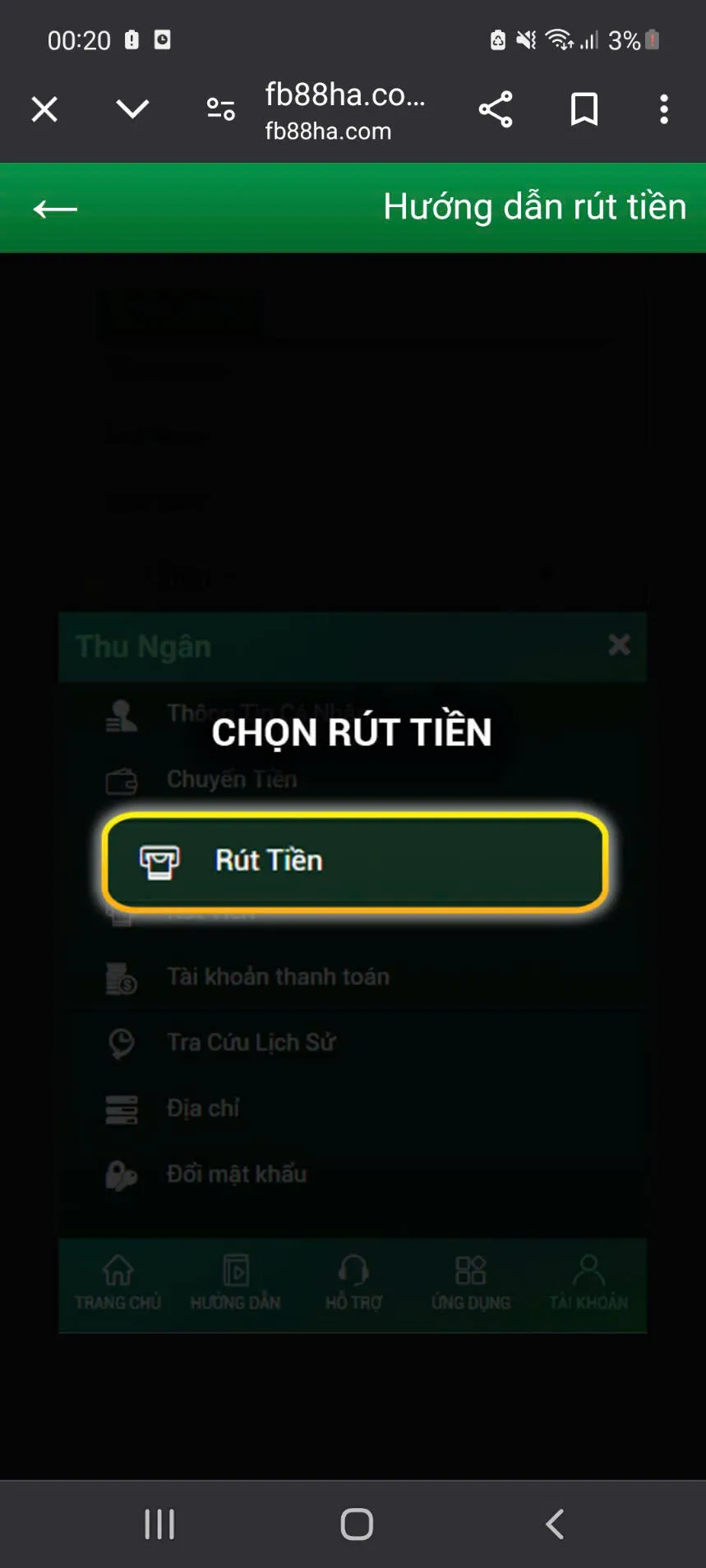

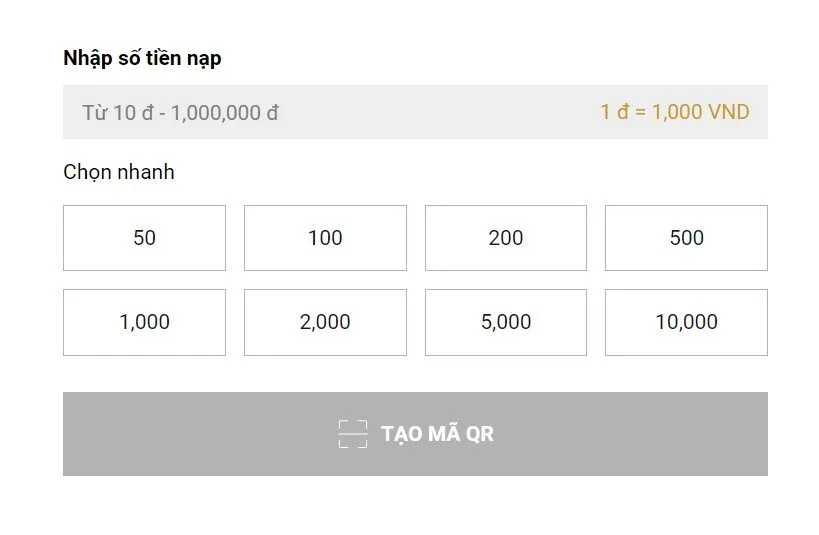

Để đảm bảo sự tiện lợi cũng như an toàn cho người chơi, nhà cái FB88 đã cung cấp nhiều phương thức thanh toán đa dạng như: chuyển khoản ngân hàng, chuyển tiền nhanh,… Hơn nữa, hình thức giao dịch nạp và rút tiền tại cổng game FB88 nhanh chóng và thao tác vô cùng đơn giản. Hệ thống cổng game có hướng dẫn chi tiết các bước giao dịch giúp người chơi thực hiện thành công ngay từ lần đầu tiên.

Quỹ thưởng lớn

Một trong những yếu tố mà người chơi quan tâm nhất khi bước vào sân chơi FB88 đó chính là tỷ lệ trả thưởng. Cổng game đã đầu tư mạnh tay với quỹ thưởng cực lớn mạnh đang chờ các game thủ chinh phục. Cơ hội để người chơi có thể kiếm bạc triệu mỗi ngày dàng hơn bao giờ hết. Hơn nữa, tỷ lệ trả thưởng tại đây đảm bảo công khai, minh bạch. Cơ chế trả thưởng của nhà cái rất sòng phẳng nên người chơi hoàn toàn yên tâm khi đặt cược.

Dịch vụ chăm sóc khách hàng tốt nhất

Truy cập vào trang chủ FB88 chắc chắn người chơi sẽ cảm thấy hài lòng về thái độ của đội ngũ nhân viên hỗ trợ. Cổng game sở hữu đội ngũ nhân viên trẻ đầy nhiệt huyết luôn sẵn sàng giải đáp mọi thắc mắc của người chơi 24/7. Trong quá trình truy cập vào cổng game hay tham gia chơi cá cược, nếu có gặp bất kỳ vấn đề gì thì người chơi có thể đặt câu hỏi thông qua các kênh hỗ trợ khách hàng như: liên hệ hotline, chat trực tiếp, chat zalo, facebook hoặc gửi tin nhắn email rất tiện lợi.

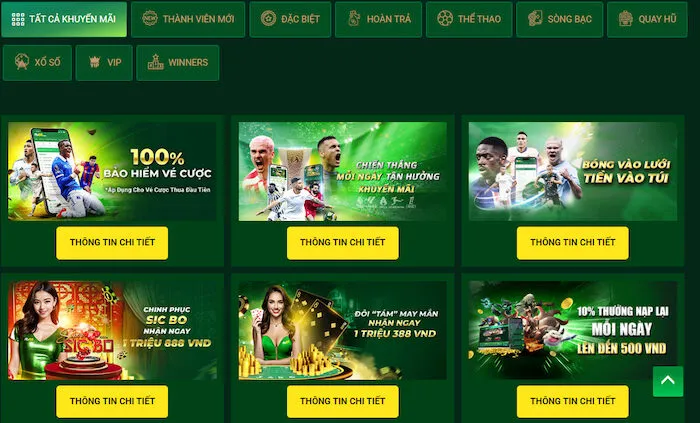

Ưu đãi lớn và cập nhật thường xuyên

Nhà cái FB88 không chỉ cung cấp những ưu đãi dành cho người chơi nhân dịp đặc biệt mà ngay cả những ngày bình thường, anh em cũng có cơ hội tham gia vào các chương trình ưu đãi siêu hấp dẫn. Một số khuyến mãi nổi bật dành cho người chơi như: thưởng 10% nạp lại mỗi ngày, đôi “tám” may mắn nhận ngay 1 triệu 388 VNĐ, 100% hoàn trả cược xâu thua, thưởng thành viên mới lên đến 2 triệu đồng, thưởng 150% tiền thưởng khi chuyển tiền quay hũ,…

Cần lưu ý gì khi truy cập vào cổng game FB88?

Để truy cập trang chủ FB88 nhanh chóng và tham gia đặt cược an toàn, gia tăng cơ hội nhận thưởng cao, newbie cần lưu ý những điều như sau:

- Tuân thủ các điều khoản quy định của cổng game, tránh mắc sai lầm vi phạm có thể sẽ bị thu hồi tài khoản vĩnh viễn.

- Đảm bảo đường truyền mạng ổn định để mang đến trải nghiệm trọn vẹn nhất.

- FB88 cung cấp nhiều trò chơi với các mức cược khác nhau. Người chơi hãy lựa chọn sảnh đặt cược phù hợp với khả năng của mình để gia tăng số tiền thưởng.

- Yếu tố quan trọng hàng đầu làm nên chiến thắng khi tham gia cá cược online tại FB88 đó chính là hiểu rõ luật chơi và cách chơi game. Vì vậy, anh em hãy đầu tư thời gian tìm hiểu luật chơi và các hướng dẫn chơi đánh bài trước khi tham gia đặt cược tại FB88. Bạn có thể tìm hiểu luật chơi và cách chơi ngay trên hệ thống do nhà cái cung cấp hoặc học hỏi kiến thức và kỹ năng từ các chuyên gia và rèn luyện thường xuyên.

- Hãy tham gia chơi game tại FB88 với một tinh thần thoải mái, không nên đặt nặng vấn đề thắng thua.

Cổng game bài đổi thưởng FB88 là sự lựa chọn lý tưởng dành cho những ai yêu thích cá cược trực tuyến. Hy vọng với những thông tin này đã giúp anh em bet thủ có thật nhiều trải nghiệm thú vị khi tham gia chơi game tại đây. Đừng quên truy cập link vào FB88 để khám phá những tựa game hot với giá trị tiền thưởng hấp dẫn nhé!

Trò chơi trực tuyến FB88

Rút tiền FB88 về tài khoản ngân hàng trong tích tắc

Rút tiền FB88 về tài khoản ngân hàng nhanh chóng trong một nốt nhạc, anh [...]

Nạp tiền FB88 – Tổng hợp 6 cách giao dịch nhanh chóng nhất

Nạp tiền FB88 hiện nay rất đơn giản. Chỉ với vài thao tác cơ bản, [...]

Top 5 game đánh bài kiếm tiền trên iPhone hay nhất tại FB88

Game bài là một trong những thể loại được nhiều người chơi yêu thích hiện [...]

Top 5+ cổng game đánh bài ăn tiền thật trên điện thoại đáng chơi nhất

Giờ đây những cổng game đánh bài ăn tiền thật trên điện thoại thu hút [...]

Khám phá top cổng game đánh bài miễn phí đáng chơi nhất 2024

Trên thị trường hiện nay quy tụ rất nhiều những cổng game đánh bài miễn [...]

Hướng dẫn cách chơi Bắn cá hải vương chi tiết cho người mới

Bắn cá hải vương hiện nay là một trong những tựa game bắn cá nổi [...]

Bắn cá đổi tiền Momo – Trải nghiệm bắn cá mới lạ, thú vị nhất

Bắn cá đổi tiền Momo hiện nay là tựa game bắn cá mang đến trải [...]

Bắn cá xèng APK – Khám phá đại dương xanh bao la huyền bí 2024

Trong thế giới bắn cá hiện nay, Bắn cá xèng APK mang đến trải nghiệm [...]